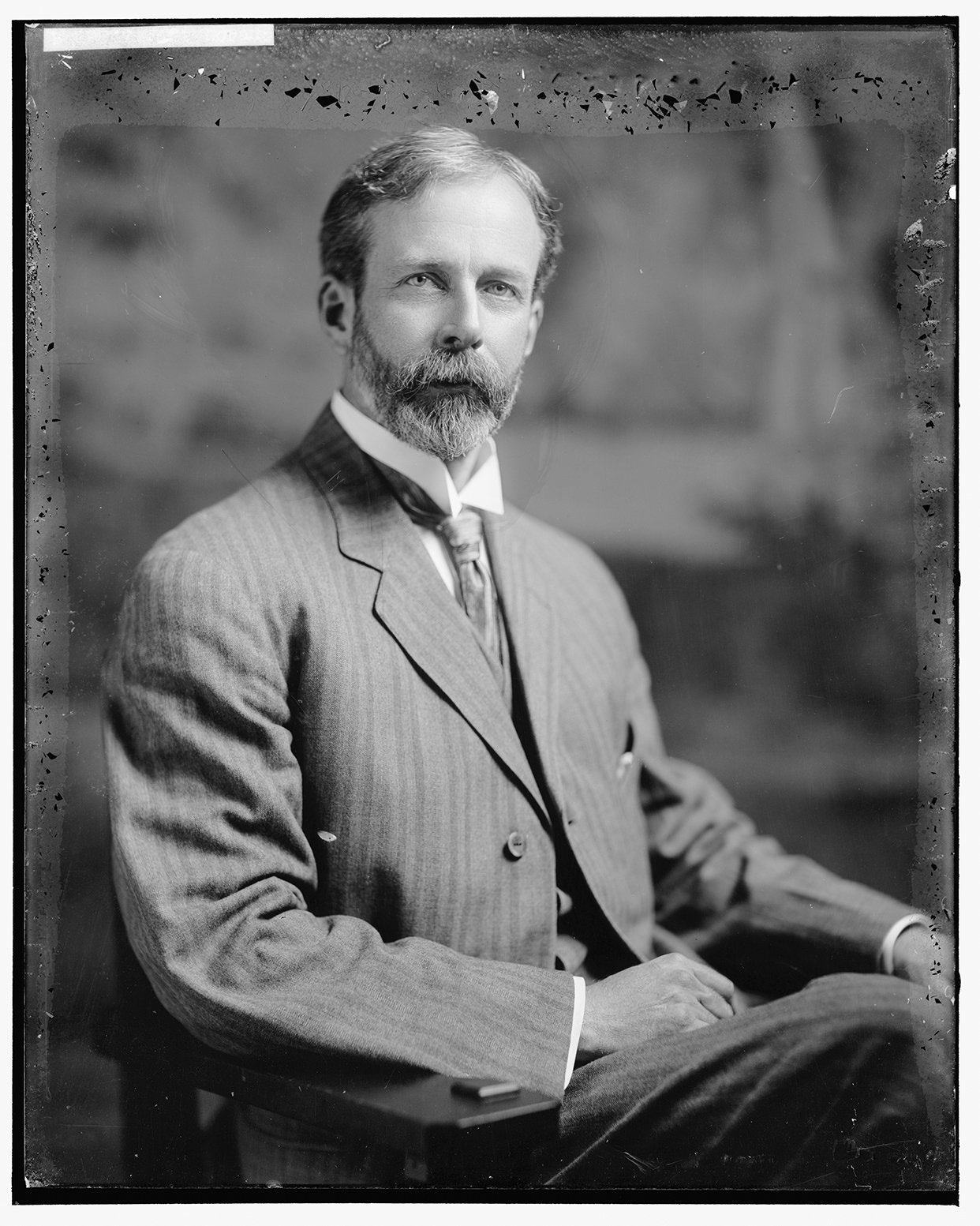

Lorado Taft

Lorado Taft: The Forgotten Sculptor Who Influenced Art in America through Education, Lecture, Critique, Writing, and Fountains

by Kyle Hanson - INFO 285 - Research Project - Applied Research Methods Historical Research

Bain News Service. (n.d.). Lorado Taft [Glass negative]. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014687242/

Introduction

Chicago has always had a lesser reputation than New York City with nicknames such as the ‘Second City’. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed 2,100 acres of structures and displaced more than 100,000 people leaving the city mostly in ruins (Chicago Architecture Center). This devastation did not stop the residents of Chicago who banded together to reconstruct and create a bigger, better city. A new Chicago was born with this community spirit whose dreamers realized they could change the world. Innovation flourished well after the fire into the new 20th century.

In the last few decades of the 1800s, architect William Le Baron Jenney designed the first skyscraper in the world, the Home Insurance Building of 1886, which sparked a new movement in high-rise construction. Architect Louis Sullivan would go onto to be known as a father of American architecture through his blend of ornamentation and functional design. Ida B. Wells used Chicago as a home base for her activism to advance the rights of black people and women. Nobel Peace Prize recipient and activist Jane Addams opened the Hull House in 1889 to educate and empower immigrants and minorities. George Pullman created and designed the world’s first industrial planned community where people lived and worked. Retail entrepreneur Marshall Field opened the largest department store in the world for his Marshall Field & Company in a building designed by Daniel Burnham. Burnham left his own mark on the city with his unique buildings across the city and for his work on urban planning in which he fought for access to parks and a freely open waterfront. Burnham was also chosen as Director of Works for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, a game-changer that would put Chicago on the worldwide map. Socialite and feminist Bertha Palmer ensured that women were an integral part of the Exposition with her Woman’s Building which was designed by and featured exhibits solely by women. Mrs. Palmer’s personal art would go on to become the foundational impressionism collection for The Art Institute of Chicago. All these pioneers are just a few of the many who left a mark on the city of Chicago during this time. Their contributions to this ‘Second City’ helped completely change and define America. Their efforts were emulated in established places like New York and Philadelphia who often take credit for these ideas. In the decades after the fire, Chicago would rise from the ashes growing from a population of just 300,000 to more than one million people (Chicago Architecture Center).

These Chicagoans are well-known in their fields of interest, but there is one Chicago artist who is always overlooked and forgotten. Lorado Zadok Taft was an American sculptor, educator, lecturer, art critic, and writer. His humble beginnings in small-town Illinois were filled with artistic mentors which inspired him to obtain an overseas education, travel throughout Europe, and return to the grand midwestern city of Chicago to create and synthesize what he had experienced. Like his Chicago contemporaries, Taft tapped into the creative, energized spirit to establish and define American art and sculpture.

Molding an Artists’ Curiosity – Origins from Rural Illinois to Worldly Paris

Lorado Zadok Taft was born in the tiny town of Elmwood, Illinois on April 29, 1860, to loving parents Don Carlos and Mary. Don Carlos Taft was a prominent professor of zoology and geology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, then known as Illinois Industrial University, while Mary Taft was a musician and artist in addition to women’s suffragist (Weller, 2014). The progressive views of his parents would create a lasting impression on young Laredo and set up his liberal beliefs for his entire career (Weller, 2014).

Taft spent his homeschooled childhood reading and exploring his surroundings until 1874 when he began taking university preparatory classes (Weller, 2014). Coincidentally, that same year, the University Art Gallery at the University of Illinois received plaster casts of Ancient and Renaissance sculpture, “one of the first of its kind in the country,” to be studied by its students (Martis, p. 159). These plaster casts were the idea of regent professor Dr. Gregory who firmly believed in promoting art education and so he traveled to Europe to find art to bring back to the university (Weller, 1985). These precious reproductions selected for the art gallery arrived damaged and Chicago sculptor James Kenis was brought over for the repairs (Weller, 1985). “For the fourteen-year-old Taft, however, their broken condition provided an opportunity to learn about the creation of sculpture by assisting [Kenis] to repair [them]” (Martis, p. 159). Taft’s assistance with the restorations was so successful that he adopted Kenis as his mentor. This experience would lay the foundations for Taft’s entire career as a sculptor (Weller, 1985). He knew what his calling was and would do everything to achieve his dreams.

Two years after his exposure to the University Art Gallery, Don Carlos and Mary brought Taft and his brother and sisters on a trip out East to see the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. He would see this International Exhibition in Philadelphia, Mount Vernon, the White House, and Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C., in addition to the sights of New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Chicago (Weller, 1985). This trip awakened Taft’s artistic curiosity even more as he discovered the treasures of the United States of America through its history and museums. He returned to Illinois motivated to finish his education, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1879 and master’s degree in 1880 from the University of Illinois.

Dr. Gregory’s art lectures at university ignited the idea that Taft should attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France (Weller, 1985). Upon university graduation, he left for Europe to begin his education in the arts. Taft spent his first few months in Paris visiting the historical landmarks, museums, and libraries to get familiar with his surroundings (Williams, 1958). The European art scene changed his whole perspective, and he was soon disappointed with the current state of art in America based on what he had seen on his trip of 1876. He studied hard and excelled at his craft. In “1881 [he] earned an honorable mention at one of the institution’s competitions [and] in 1882 the Paris Salon accepted a sculpture by Taft” (Martis, 2005, p. 160). In Paris, he was given the opportunity to work alongside the greatest artistic talents from around the world. This education was the “best the period could offer, and the most competitive” (Williams, 1958, p. 152). Though Taft loved Paris, he would return to the United States to help Americans see how beautiful and necessary art should be.

Literature Review

Because Taft has been mostly forgotten, he has not been studied or written about as much as others of his time. The few scholars who have remembered Taft clearly understand how important his contributions and legacy are to sculpture and the American public. Together, they have posed that Taft made an impact on the American view of art based on his career as an educator, lecturer, art critic, and writer. These four fields, to which Taft excelled and impacted, allowed him to make enough money to finance his projects as an artist of sculpture.

Taft as Educator

Most of Lorado Taft’s American classmates at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts returned to the United States to start their careers out East in places like New York and Philadelphia while Taft returned to his home state of Illinois in 1886 where he had fond memories of his childhood (Williams, 1958). He settled in Chicago as a newly graduated and virtually unknown artist. After studying abroad for several years, Taft noticed that Americans had a different relationship to art than their European counterparts who had free, accessible, and beautiful art everywhere. Researcher Martis (2005) believes Americans likely had this limited view of art because industrialization limited their appreciation for handcrafted objects, “so progress in support of the visual arts was difficult in Taft’s view” (p. 174). Americans were so focused on the industrial revolution that creativity and fine workmanship were being completely disregarded; however, Taft realized he could create appreciation and excitement for art through education. He began teaching classes at The Art Institute of Chicago upon his arrival. Taft became aware that he was a natural instructor while standing in as teacher of clay modeling at the University of Illinois between 1878-9, so the role of educator was an obvious place to begin his new career (Weller, 1985). According to Taft, another reason Americans did not appreciate art was because there was no formal art education taught in schools, and most students graduated without ever seeing art in real life (Martis, 2005). “He believed that reaching younger students would profoundly shape their recognition of beauty in the world” (Martis, 2005, p. 172). Taft understood that teaching students was the best way to share his love for art since young minds are more receptive to new ideas and change than adults. He could mold his students’ minds the way he molds his sculptures. According to researcher Williams (1958), Taft was “a patient and considerate instructor… who ha[d] an influence on his students” (p. 208) By remaining kind and approachable, he built strong relationships with his students that would extend outside of the classroom and into their careers.

Unknown. (1899). Lorado Taft's Art Institute class [Photograph]. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://archon.library.illinois.edu/archives/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=7631

Taft founded the Department of Sculpture at the Art Institute, bringing it from one simple modeling class to an entire art focus (Williams, 1958). He also opened his department to women at a time when they were often excluded from educational opportunities and careers in the arts. This likely stems from his mother’s participation in the women's suffrage movement which made an impact on his views beginning in childhood. Taft’s personal studio was also located in the Fine Arts Building at the time which shared offices with the Chicago Equal Suffrage Association and Cook County Women’s Suffrage Party (Garvey, 1988). He would have the opportunity to learn about these groups and become friends with many early feminists including scholar & poet Harriet Monroe and pioneer theater instructor Anna Morgan (Garvey, 1988). Taft also taught clay modeling and provided art lectures at friend Jane Addams’ Hull House for the city’s immigrants, giving them a way to assimilate into their new-world surroundings (Musacchio, 2014). This helped bring the community together since art is a universal in which everyone can participate. Taft created a legacy as an educator by teaching young students, women, and immigrants at a time when most would have found this to be socially unacceptable.

Hergt, E. (1896). Modelling class at Art Institute [Photograph]. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://archon.library.illinois.edu/archives/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=2810

Taft as Lecturer

Lorado Taft would give “more than two thousand lectures over the course of his career, to audiences small and large, young and old, amateur and professional, across this country and to American troops abroad, ranging from the clay talk to analyses of art historical topics to social commentaries pleading for a popularization of art” (Musacchio, 2014, p. 17). Taft likely realized he was a natural public speaker after he was chosen to give the class prophecy for his class of 1879 at the University of Illinois (Weller, 1985). He commanded this audience by talking about his passion for the arts and his dreams for the future. Merely teaching students at the Art Institute was not enough to change the unfortunate state of art and sculpture in America so Taft also began giving lectures to the public. “He believed that most Americans were ignorant of art in general” (Musacchio, 2014, p. 18). Taft’s lectures became the perfect venue to promote his theory that the world can become more beautiful filled with art, so he used his good looks and charm to win over his audiences. “Taft was so much in demand as a lecturer that multiple bookings at times forced him to send others in his place” (Garvey, 1988, p. 47). His popularity would soon earn him the reputation as an authority on public art not only in the Midwest but around the United States.

In 1919, Taft partnered with community advisor, academic administrator, and educator Dr. Robert E. Hieronymous (known by Taft as Dr. Hi) to create the Art Extension Committee of Illinois (Weller, 2014). Through this committee, Taft and Dr. Hi would lead summer excursions to the most beautiful, historic, and artistic places across the state of Illinois, such as the Illinois River, Mississippi River, and Abraham Lincoln heritage sites (Weller, 2014). This committee work brought people closer to art and history by allowing them to experience it in person. The energy and excitement of these trips inspired Taft in return, which can be seen reflected in his own sculptural works of the time. When the Great Depression hit, Taft still “commanded the highest fees” for his lectures, which would be a testament to his brilliance of captivating and moving an audience (Williams, 1958, p. 207).

Taft as Critic

Lorado Taft “also gained public attention by writing art criticism…he did this mainly to supplement his income, although he was also aware of its publicity value” (Martis, 2015, p. 164). Taft’s education at the École des Beaux-Arts, in addition to his travels across Europe to see the World’s greatest art, gave him the knowledge to be able to critique art. He could tell if a piece of work was great simply through his expert way of seeing. “Taft set high standards and was not reticent about criticizing the work of others” (Duis, 1976, p. 88). While teaching at the Art Institute, he would set aside time twice a week to critique the work of his students. Though he was strong in his opinions on what constituted great art, “his suggestions, unfailingly kind and courteous, were respected, as was he” (Williams, 1958, p. 163). Like his role as an educator, Taft’s ability to remain humble and kind during critique helped strengthen his reputation because people valued and trusted his opinions.

In 1894, Taft founded the Central Art Association with writer and brother-in-law Hamlin Garland to promote art in small towns across the Midwest. Through critique, lectures, and traveling art exhibitions, the Association helped bring art to these small towns. They wanted to spike the curiosity in those that were never given the opportunity to see or create art. New and upcoming artists were often chosen to showcase their works at these shows giving artists valuable exposure at critical points in their careers (Duis, 1976). According to Garvey (1988), Midwestern artists were often dismissed by their Eastern counterparts, and the work of the Central Art Association was meant to empower them. Taft and his colleagues at the Association also created a “bureau of criticism” to “help aspiring artists evaluate their own work” (Duis, 1976, p. 88). These critiques would help mold aspiring artists and give them the honest feedback crucial for their growth while giving them the tools to be their own critic. Taft wanted everyone to find their inner artist but also to formulate their own opinions and emotional reactions to art.

Unknown. (1910s). Lorado Taft in studio [Photograph]. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://archon.library.illinois.edu/archives/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=1526

In 1890, Taft created a portrait bust out of butter for the Masonic fair in Detroit (Simpson, 2007). He understood that he could also promote the arts by serving as critic for many popular social events. Taft became a regular judge for the annual Ivory Soap carving contest where winners would have their creations publicly displayed in grand settings like the Marshall Field’s Department Store (Musacchio, 2014). He would also judge Chicago’s annual snow sculpture competition during the long, harsh winters. Like his teachings and lectures, Taft helped art become publicly accessible through his variety of critiques. With his work at the Central Art Association and as a judge for local community events, Taft “became even more interested in the application of art to everyday life” (Williams, 1958, p. 165). He understood that one does not have to be formally educated to create or appreciate art: it can be made and enjoyed by all.

Taft as Writer

Though Lorado Taft excelled as an educator, lecturer, and critic, his writings were among his most important contributions to America. Taft was a natural writer as evidenced by his letters back home while studying in Paris. He exchanged correspondence regularly with his family who kept every single one over the years. Upon settling in Chicago, Taft began to write about the importance of sculpture for many newspapers and arts magazines. He started at “the Tribune over other local papers at the time because they had the reputation for paying the highest rates to free-lance authors” (Garvey, 1988, p. 62). Since he came to Chicago as an unknown artist, writing helped pay the bills, alongside teaching and lecturing. Taft would take the most important segments of his lectures and publish them in the Chicago Inter Ocean which furthered his authoritative reputation (Garvey, 1988). In just a few shorts years, he would already have “at least forty-four articles in twenty different magazines” (Weller, 2014, p. 123). Taft also became a regular contributor to art journals such as Brush and Pencil, Arts for America, The Sketchbook, and The Chicago Record.

Because of his successful writings in many newspapers and journals, publishing magnate, the Macmillan Company, chose Taft to create a publication on sculpture for their History of American Art series which led to his first published book, the History of American Sculpture in 1903 (Garvey, 1988). As Williams (1958) states, this would become “without a doubt the most important thing for Taft as an influence in American art” (p. 175). It was the first detailed overview of American sculpture ever published and would be studied in art circuits for the next half a century. The book served as a chronology of American sculpture and was accompanied by photos of the most famous works. This book furthered Taft’s desire to bring art to the people because even if they could not see it in person, they could consume it through words and pictures. This important publication “confirmed his position as one of the foremost authorities and most cogent writers on American art” (Garvey, 1988, p. 63).

In 1921, Taft would produce his second and last book, Modern Tendencies in Sculpture. This was a completely different format than his first with sections based on six lectures from the Art Institute. He ends the book with the idea that it is not too late for Americans to create great sculpture, and the best is yet to come (Taft, 1921). Believing in a better future for the state of American art shows that Taft was also an optimist, yet another skill that helped him affect change. Through his books and published writings, “it is quite possible that Taft published more than any other artist of his generation” (Weller, 2014, p. 123).

Methodology

My research began with an internet search for Lorado Taft which led to numerous encyclopedic entries in addition to the few books that have been written about him. From there, even more sources were found by looking at the references from those works in addition to searching databases accessible online through the King Library at San José State University. This is where the scholarly journal articles pertaining to Taft were found. My Historical Research Methods professor, Dr. Donald Westbook, recommended two important dissertations which helped provide a lot of the foundational insight for Taft’s legacy.

I did not have an area of focus when I started other than knowing that I wanted to highlight Taft’s achievements. It became clear that scholars and authors collectively noted Taft’s contributions to America through his successes as an educator, lecturer, art critic, and writer without even talking about his sculptures. This became the basis for the Literature Review; however, the paper begins with a section on Taft summarizing his childhood to education at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris because it helps reveal how his opportunities and experiences as a child and student informed his decisions throughout his career.

Only after discussing his upbringing and legacies in other fields other than sculpture could I then attempt to paint a picture of Taft’s successes as an artist of sculpture. The following section is a discussion of four of his most notable works that inspired all who witnessed them with two still existing today. These include Taft’s first big break at the 1893 Columbian Exposition followed by three innovative water fountains which are supported by additional sources including newspaper.com. These historical print sources allowed me to interpret exactly how the public felt about Taft’s works as they were unveiled through Chicago Tribune papers among others. This helps frame the mindset of the past while informing the present.

McIntosh Battery and Optical Co. (1893). World's Columbian Exposition, Horticultural Building [Lantern slide]. The Art Institute of Chicago. https://artic.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/mqc/id/26130/rec/121

Discussion

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 – Taft’s Big Break

“In 1876, Lorado attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia where for the first time he encountered a large-scale gathering of original works of art” (Weller, 2014, p. 240). As discussed earlier, this family trip to the exposition was a life-altering experience for young Taft. He would go on to create sculptures for six world fairs throughout his career. Taft enjoyed teaching, lecturing, and writing; however, he began these jobs because it was one of the few guaranteed ways to bring in money as a young artist. Throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, he was also working steadily by creating portrait busts and war memorials, though this was not the work he was passionate about. Taft’s big break came in 1892 when he was selected to create two sculptures for architect pioneer William Le Baron Jenney’s Horticulture Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Taft believed in creating art that blended into their surroundings and so he created two floral sculptures at the entrance of the Horticulture Building to welcome visitors from around the around. He called these Sleep of the Flowers and Awakening of the Flowers with each containing “three main figures, about eight feet high, with smaller attendant cupids, a faun, and rich vegetation” (Weller, 2014, p. 75). Taft wanted to convey the idea of flowering plants that open and close by the changing light of day as seen with Sleep draped in clothes while Awakening has arms raised to the sky.

Taft hired many of his students at the Art Institute as assistants at his personal studio. He brought these pupils, which were mostly women, to help at the exposition after Director of Works for the Fair, Daniel Burnham, noticed that exterior work on most buildings for the fair was falling behind. Taft became shop foreman in charge of sculpture to ensure completion across the entire fair (Garvey, 1988). These women artists became famously known as the ‘white rabbits’, a legacy for which Taft became “credited with helping to advance the status of women as sculptors” (Glessner House). ‘White’ refers to the nickname of the fairgrounds which were buildings painted in all-white while “’Rabbits’ bears witness to the biases at the fair among female and male professionals” (Decker, 2019, p. 48). Taft and his team of talented sculptors brought to life much of the sculptural works for many of the fair’s buildings, bridges, and grounds.

These ‘white rabbit’ women also made an even greater impact at the fair with additional art commissions. Enid Yandell who was hired by Bertha Palmer to design two dozen caryatids for the roof of the Woman’s Building. It was the biggest project Yandell had ever been tasked with, and she would earn an Exposition Designer’s Medal, one of only three women to earn such awards. Daniel Burnham presented Yandell with the award and called her a colleague which was a rare feat for a woman in those days (Decker, 2019). Another woman, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, created an eight-foot-tall sculpture for the Illinois State Building (Martis, 2005).

Unknown. (1892). Lorado Taft sculpture studio in the World's Columbian Exposition Horticulture Building [Photograph]. Chicago History Museum. https://collections.carli.illinois.edu/digital/collection/chm_pp/id/46

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was Taft’s first big break as a sculpture artist and one of his most memorable life experiences. Established and rising artists from all over the country came to Chicago to create art for the exposition, and this afforded Taft the opportunity to meet and work alongside them all. This challenged him creatively and provided the exciting and stimulating environment necessary to create great art (Garvey, 1988).

“The 1893 Columbian Exposition gave American sculptors an opportunity not only to demonstrate their technical skill but also to express national qualities that seemed to [Taft] in advance of European work. He believed that a public was being developed that would for the first time recognize and support the importance of sculpture” (Weller, 2014, p. 128).

The entire world would witness the amazing art & sculptures of the fair and return home with a desire to add art to their own communities. This once again fulfilled Taft’s vision of making the world more beautiful with art.

Nymph Fountain 1899 – Taft Pushing Boundaries

Lorado Taft was clearly inspired by the grand architecture of the Columbian Exposition with its extravagant buildings, parks, lagoons, and fountains. Most of his most famous works in the years that followed were fountains. In 1899, ten female students at the Art Institute, under the direction of Taft, created what became known as Nymph Fountain. As a culminating project for his students, this temporary fountain featured ten female nude figures bathing in the water. It was installed adjacent to the Art Institute and was also meant to create “interest in civic beautification” through public sculpture by waking up the Chicago public (Garvey, 1988, pp. 26-28). Taft and his students quickly and quietly installed the fountain by night in time for a morning debut on June 16. This new sight along bustling Michigan Avenue caused some of the biggest rush-hour traffic Chicago had ever seen. News outlets arrived with the crowds to see the fountain and police were called in to control the crowds (Garvey, 1988). As printed in the Chicago Tribune on June 17, “after a day’s trial the prevailing sentiment seemed to be that the fountain was a beautiful piece of sculpture, that is was not objectionable, and that the young women who made it under Lorado Taft’s direction deserved credit for excellent and lifelike execution.” (1899, p. 1).

Unknown. (1899). Lorado Taft and students, Nymph Fountain [Photograph]. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Though the consensus was that the fountain was a great example of what public art should be, it was completely vandalized a month later. According to the Boston Evening Transcript, “many of the nymphs had their hands and some of their arms broken off, while in the bodies of others holes had been punched, making them unsightly objects” (1899, p. 4). The fountain was never intended to be permanent so was more susceptible to vandalism. Taft understood that the country did not approve of the public display of nude art so created this installation to show that nudity could “be appreciated for their beauty of form and technique” (Martis, 2006, p. 180). Though it was ultimately destroyed after only a month, Nymph Fountain woke up the public by pushing society’s limits of nude figures and inspired the need for more accessible public art while also promoting women in the arts.

Fountain of the Great Lakes 1913– Taft’s First Major Public Commission

One of Chicago’s most famous public fountains is Lorado Taft’s Fountain of the Great Lakes. It was created between 1907 and 1913 with a grant from the Ferguson Monument Fund, which was a one $1 million dollar fund left behind by lumber tycoon Benjamin Ferguson to create public art in Chicago (Borzo, 2017). The Ferguson Fund was “intended to improve the city’s appearance, thus corresponding to Taft’s own efforts” (Martis, 2005, p. 168). Taft knew that public art was necessary to make a place more beautiful, and he believed that it should tell a story of its surroundings. With his established relationship with the Art Institute, the fountain was an extension of the museum placed just outside its walls for everyone to see. The Art Institute itself is the only structure east of famous Michigan Avenue in 310-acre Grant Park which serves as a green, public gateway to Lake Michigan.

Fountain of the Great Lakes was born out of a conversation with Daniel Burnham who was disappointed there was never a sculpture to pay tribute to the five Great Lakes at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The finished fountain contains five female figures, one for each lake, that represent “the academic ideals of balance and harmony in composition, as well as beautiful form” (Martis, 2005, p. 168). Special consideration was given to the importance and size of each lake in the final fountain.

“High above the others is Superior, twenty-five feet over the fountain’s base, holding aloft her shell and emptying its contents into another held by Michigan, who sends her cascade on to Huron. From there water passes to Erie and, finally, on the ground level, Ontario receives the stream of water and sends it toward the ocean” (Weller, 2014, p. 169).

The fountain was officially unveiled to the public on September 9th, 1913, and was Taft’s first major public commission. Taft gave a speech alongside Charles L. Hutchinson, president of the Art Institute, and John Barton Payne, president of the Board of South Park Commissioners. They praised the fountain as one of the greatest gifts the public had ever been gifted and called Taft “one of the few great sculptors of the age” (Weller, 2014, p. 171). The next day, the Chicago Tribune would print that this work would give rise to the “rapid progress of art in Chicago” (1913, p. 6). Fountain of the Great Lakes allowed Taft to create permanent change through art in Chicago and continues to stand today for all who walk by and watch the water flow between the female figures of the great lakes.

Kyle Hanson. (2015). Lorado Taft Fountain of the Great Lakes [Photograph]. Creative Boulevards.

Fountain of Time 1922 – Taft’s Legacy of Time

In 1906, Lorado Taft moved his art studio from the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue to what he would call Midway Studios on the South Side of Chicago. This was located across from the University of Chicago on a stretch of green known as Midway Plaisance Park which connects Jackson Park with Washington Park. The Midway Plaisance was the mile-long carnival area at the 1893 Columbian Exposition which featured “carnival rides, performances, food stalls, and inhabited ‘villages’ purporting to display architecture and customs from around the world” (Elliott). This is also where the famous Ferris Wheel made its worldwide debut, becoming a symbol of the fair and introducing the world to new heights. Taft loved this location because of his fond memories of working at the exposition so moved his studio here which would be much larger than his previous location. Taft stopped teaching at the Art Institute “but a concern for the young artist did not. His habit of hiring student sculptors as studio assistants continued, affording them both financial help and valuable practical experience” (Williams, 1958, p. 175). This new studio would provide adequate housing for his assistants.

Taft saw the empty green space of Midway Plaisance Park, which had once been filled with bustling excitement, as an opportunity for a great public sculpture. He began creating models in 1907. After the success of the Fountain of the Great Lakes in 1912, Taft was given the green light to begin formalizing his vision through another grant with the Ferguson Monument Fund in 1913 (Weller, 2014). This project would be called the Fountain of Time. According to The Dial, a literary magazine of its time, “this project is of far more than local import, aiming at the creation of an artistic monument which shall be one of the most beautiful in the world, it deserves the widest publicity” (1913, p. 121). All the eyes of Chicago, and the globe, were curious of the magnitude of such a project during its initial announcement. The Dial goes on to write that the fountain will also honor the legacy of the fleeting memories of the Columbian Exposition by bringing a permanent, long-lasting work of art. Those in charge of the Ferguson Monument Fund believed that Taft had the creativity and “genius” necessary to complete such a project (The Dial, 1913, p. 122). It took another nine years of careful design, planning, and craftsmanship for the final fountain to be finished and unveiled to the public through dedication on November 15, 1922. Taft told the audience through his opening speech that this project helped fulfill his “lifelong dream of transforming the green terraces of the Midway into a modern conception of the famed Parthenon of ancient Greece” (Chicago Tribune, 1922, p. 3). This public work of art was Taft’s way of bringing his inspirations from his European education and travels back to America.

Weller (2014) describes the Fountain of Time with an introduction of the Father Time figure on one side of the fountain: “an immovable personification of Time gazes across a pool at approximately eighty figures passing in a vast procession (p. 156) while Hall & Jones (2005) best summarize the opposite figures:

“Beginning with birth of humankind at the north end of the sculpture, swirls of water gradually rise to form the crest of a low wave; a woman emerges half-formed from the swell, and behind her, a crouching man grasps its crest. The water/wave motif, symbolic of the origin of life and eternal repetition, is integral to the sculpture: the wave carries the figures forward, accenting their drapery and posture to create a dramatic sense of movement. At the apex of the group, a mounted warrior looks rigidly ahead, surrounded by solders, camp followers, and refugees. Other figures range from parents and children to embracing lovers, clerics to dancers; the sculptor is said to have modeled one group of maidens on his daughters and even portrayed himself followed by one of his workmen. At the south end, as death approaches, a man and a woman merge back into the water” (p. 80).

Kyle Hanson. (2022). Lorado Taft Fountain of Time [Photograph]. Creative Boulevards.

These descriptions help show just a few of the complexities of why the fountain took fifteen years to create and complete. Fountain of Time became a masterpiece and helped strengthen Lorado Taft’s legacy. It was also a project of innovation as it became the largest sculptural work to be cast in concrete (Martis, 2005). Taft worked alongside John Joseph Early who pioneered a new kind of cement by mixing pebbles into the plaster giving it a more textured look in addition to color for the final casting (Weller, 2014). This also kept the cost of construction down.

“Both Earley and Taft considered the finished sculpture a technical and artistic triumph, imagining that the relatively low cost of its technique would put public art within reach of many small towns. At the time, the project received a great deal of attention from the cement industry, for which it still remains a focus of great interest” (Hall & Jones, 2005, p. 82).

This low cost would allow small communities across the country access to more affordable sculptures, once again furthering Taft’s lifelong goals of bringing art to everyone.

Since the innovative use of cemented concrete was new, Taft and Earley “did not take into consideration problems of pollution, security, and vandalism—in short, the ravages of time” (Weller, 2014, p. 163). They could not have known the longevity of this newly created material and they both passed away long before time would begin to alter the Fountain of Time. Despite all of this, a new field of sculptural conservation emerged in the 1970s. “Conservators adopted a comprehensive approach that began with investigation into original fabrication techniques; archival searches for historic documents and construction plans; scientific analysis and materials testing; and concluded with a detailed, photo-documented condition report and treatment proposal” (Hall & Jones, 2005, p. 84). Taft’s innovative use of materials would inspire a new wave of sculptural appreciation: conservation. Historians would start preservation by studying original artist plans and materials. This shows that Taft’s legacy would have unintended effects several decades after his passing. The Art Institute, which had a strong relationship with Taft during his entire career, along with the Chicago Park District and University of Chicago, helped fund a several-decade restoration of the fountain to return it to its original glory. Fountain of Time still shines tall in the Midway for all who want to visit and cements Taft’s legacy as a Chicago pioneer of innovation and artistic change.

Kyle Hanson. (2022). Lorado Taft Fountain of Time Self Portrait [Photograph]. Creative Boulevards.

Conclusion

Lorado Zadok Taft was a Chicago pioneer who helped change the American view and opinion of art. In the words of Martis, “he described art as a search for beauty, and beauty as a revelation of God. He believed that all men and women had the potential to be students of beauty, which would bring soothing and charm to dark lives” (2005, p. 170). Taft wanted everyone to experience art and believed that art should blend naturally into its surroundings. He was able to promote his opinions through teachings at the Art Institute, public lectures, critiques, and published writings which gave him the funding, recognition, and authority to create innovative sculptures. Taft’s parents, feminist mother Mary and intellectual father Don Carlos, provided the supportive childhood he needed to become educated and dream big while remaining humble and respectful to all he encountered. He taught and hired women at his studio during a time when women were not given opportunities in the arts. This was best seen at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition which showcased to the world the talents of American artists. Taft’s projects pushed the boundaries of Victorian society by exposing the public to nude figures with Nymph Fountain, while his Fountain of the Great Lakes would go on to become one of Chicago’s first and most famous public art commissions. Fountain of Time would honor the legacy of the Exposition while permanently cementing the different variations of humanity through time. His innovative use of materials would help establish new methods of preservation decades down the road. Like many pioneers of the Chicago renaissance in the decades following the fire, Lorado Zadok Taft deserves to have his legacy remembered.

References

Borzo, G. (2017). Chicago's fabulous fountains. Southern Illinois University Press.

Boston Evening Transcript. (1899, July 17). Nymphs’ fountain at Chicago ruined. Boston Evening Transcript, p. 4.

Chicago Architecture Center. (n.d.). The great Chicago fire of 1871. Architecture.org. https://www.architecture.org/learn/resources/architecture-dictionary/entry/the-great-chicago-fire-of-1871/

The Chicago Daily Tribune. (1899, June 17). Nymph group in favor. Chicago Tribune, p. 1.

The Chicago Daily Tribune. (1913, September 10). In brief. Chicago Tribune, p. 6.

The Chicago Daily Tribune. (1922, November 16). Lorado Taft’s plan of midway sculpture told. Chicago Tribune, p. 3.

Decker, J. (2019). Enid Yandell: Kentucky’s pioneer sculptor. University Press of Kentucky.

The Dial (1913). A dream to be realized. The Dial, 54(640), 121-122. https://archive.org/details/dialjournallitcrit54chicrich/page/120/mode/2up

Duis, P. (1976). Chicago: Creating new traditions. Chicago Historical Society.

Elliott, K. K. (n.d.). The world’s Columbian Exposition: The midway. Smart History. https://smarthistory.org/worlds-columbian-exposition-midway/

Garvey, T. J. (1988). Lorado Taft and the beautification of Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Glessner House. (n.d.). White rabbits. https://www.glessnerhouse.org/story-of-a-house/tag/White+Rabbits

Hall, B., & R. A. Jones. (2005). Time and tide: Restoring Lorado Taft’s fountain of time: An overview. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 31(2), 80–112. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4104461

Martis, S. (2005). Famous and forgotten: Rodin and three American contemporaries (Order No. 3177658) [Doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University] ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection. (305007274). http://search.proquest.com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/dissertations-theses/famous-forgotten-rodin-three-american/docview/305007274/se-2

Musacchio, J. M. (2014). Plaster casts, peepshows, and a play: Lorado Taft’s humanized art history for America’s schoolchildren. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 48(4), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.48.4.0017

Simpson, P. H. (2007). Butter cows and butter buildings: A history of an unconventional sculptural medium. Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc., 41(1), 1-19. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/511405

Stolte, K. M. (2019). Chicago artist colonies. History Press.

Taft, L. (1921). Modern tendencies in sculpture. Art Institute of Chicago.

Weller, A. S. (1985). Lorado in Paris: The letters of Lorado Taft, 1880-1885. University of Illinois Press.

Weller, A. S. (2014). Lorado Taft: The Chicago years. (R. G. La France, H. Adams, & S. P. Thomas, Eds.). University of Illinois Press.

Williams, L. W.,II. (1958). Lorado Taft: American sculptor and art missionary (Order No. T-03987) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Chicago] ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection. (301951135). http://search.proquest.com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/dissertations-theses/lorado-taft-american-sculptor-art-missionary/docview/301951135/se-2